Understanding trauma in our bodies

Sometimes the effects of trauma can lead to behaviour that might look like unsafe or harmful. These behaviours we use to cope with trauma can lead to being judged, shamed, isolated, punished or criminalised.

Learning how trauma can change our brains helps us see that these behaviours that might look unsafe or harmful can be ways we cope with overwhelming life stories.

This does not mean we should not be held accountable for our actions. But that as a community, building spaces where our bodies feel consistently safe will help us all make more fulfilling choices.

How trauma affects our brains

When we experience trauma, our brains alert system is activated. This suppresses the parts of our brain that control learning, memory, reasoning and impulse control.

Trauma can also change this alert system to be bigger and more sensitive. This means our reactions to possible threats will be quicker and more powerful and activated to smaller events.

This can mean that we are in an alert or anxious state even in a safe environment.

As the brain is using all its energy keeping us safe when in this state, there is less energy for learning, memory, reasoning, and impulse control. This can have long-term effects on our brains development.

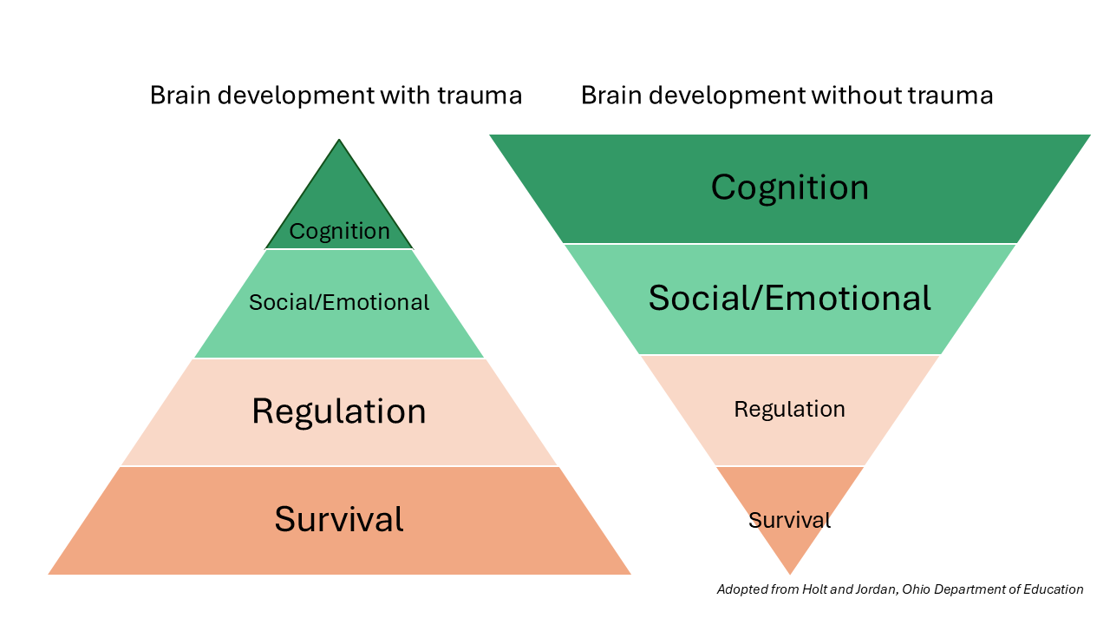

How adverse childhood experiences affect our brains

As our brains grow, they use our experiences to understand how safe our environment is and what resources are available. It then develops to survive in that environment.

Adverse childhood experiences can tell our brains our environment is unsafe and that resources, such as food or companionship, are limited. The more or worse the adversity is, the more unsafe our brains tell us our environment is.

Dr Haley Peckham makes sense of this by likening experiences to rain and our brains to the land. One drop doesn’t have much impact. But a rainstorm can create streams and carve paths into the earth.

One adverse experience, one drop, may not have an effect. But repeated experiences carve out neural pathways and changes the landscape of our brains.

If our brains believe our environment is unsafe or doesn't have enough resources, they will develop to focus on detecting threats and surviving. This means there is less energy to develop of tools to regulate, to control thoughts and actions, and to create long-term goals.

This means that unsafe or harmful behaviours can be tools our brains have developed to meet needs and survive in an unsafe, resource lacking environment.

This can look like a person who is overly alert or quick to anger because growing up they witnessed family violence. It could look like a person with poor impulse control because didn’t have enough food growing up.

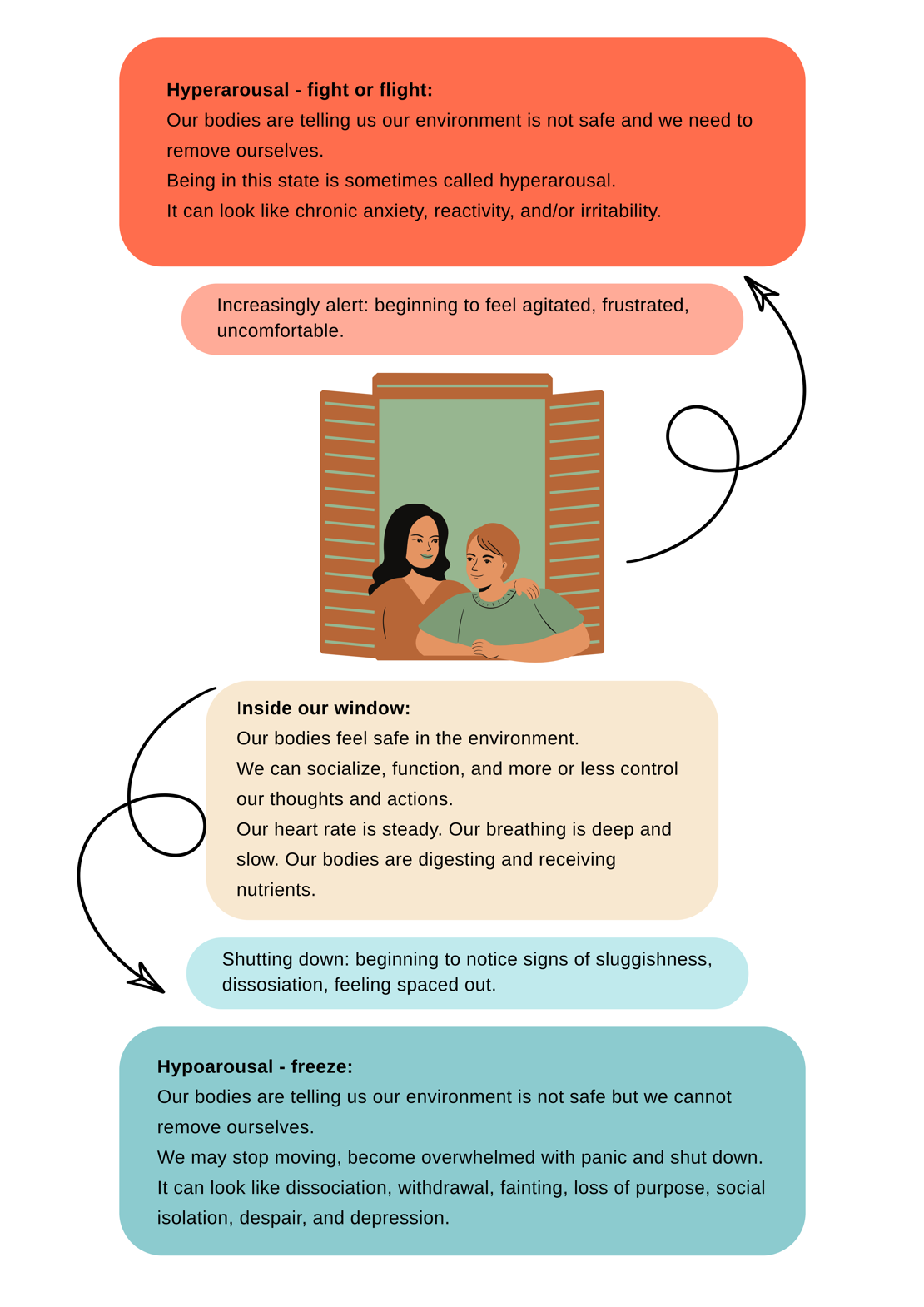

How trauma affects our bodies

When our bodies detect a threat our heart rate and breath will increase, and our digestion will slow, telling us we are unsafe.

When our heartrate and breathing is very fast, and our digestion stops, we enter survival mode. This is not a choice. It is our bodies trying to keep us safe possibly before we even realise there is a threat.

In this state our bodies are getting less nutrients. If we enter this state frequently or for long periods of time our bodies may not be getting the nutrients it needs to keep us healthy. This can lead to health implications, such as organ failure.

| Stage one: flight or fight, or hyperarousal. | Stage two: freeze or hypoarousal. |

| Our bodies fill with energy and tell us to remove ourselves from the environment. It can look like chronic anxiety, reactivity, and/or irritability. | Our bodies feel like they can’t remove us from the threat, so they shut down. It can look like dissociation, withdrawal, fainting, loss of purpose, social isolation, despair, and depression. |

These stages can happen separately or at the same time.

The window of tolerance

Within our window of tolerance, we feel safe and regulated, our heart rate and breathing are slow, our digestive system is working. We can socialize and more or less control our thoughts and actions.

If we start to leave our window, if we start to panic, may still be able to function but we need to regulate (calm) ourselves.

If we leave our window, we won’t feel safe, we won’t be able to socialise or think rationally. We need to regulate (calm) ourselves before we can think rationally or socially connect.

Getting back into our window

| Stage | Signs | Regulating (calming) steps |

| Early-stage | Slight quickening of breath and heart rate. | Notice the breath. See if it can deepen and slow. This can change our body's signals and reassure our bodies we are safe. |

| Early-stage | Slight quickening of breath heart rate. | Calm and empathetic conversation. Soothing interactions can slow our heart rate and breathing, which tells our bodies we are safe. |

| Intermediate-stage | Fast breath and heart rate, being around people feels threatening, uncomfortable or unsafe. | Calming movements can help release stress hormones and activate your brain. |

| Late-stage | Heart rate and breathing are very fast, feel panicked, might notice signs of agitation, aggression, or anxiety, or becoming vague or shutting down. People and the environment feel threatening, uncomfortable and/or unsafe. | Change environments to somewhere we feel safe, familiar, with low stimulation. Work through the previous steps until calm. This can take a while, so we need to be kind and patient with ourselves and/or others. |

For more activities go to our Self-care strategies for becoming trauma-informed page.

Coping with trauma and adverse childhood experiences

The tools our brains develop depends on how safe our brains believe the environment is. In an unsafe environment, these tools may appear unsociable or harmful to ourselves or others.

| These tools can look like: | Which leads to overrepresentation in: |

|

|

Seeing these tools as rationally chosen behaviours can lead to punishment. Punishment can increase trauma responses as it confirms the bodies belief that the environment is unsafe.

When we see that these behaviours are attempts to meet needs and cope, it is obvious that we need safe and supportive environments to engage in fulfilling behaviour.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be held accountable for our actions, but that safety and support need to be a priority.

Prevalence of coping adaptations

People who have experienced 4 or more ACEs are:

- 20X more likely to be incarcerated in their lifetime

- 12.2X more likely to have attempted suicide

- 10.3X more likely to have injected drugs

- 6X more likely to have had or caused an unintended teenage pregnancy

- 4.6X more likely to suffer from depression

- 2.5X more likely to contract a sexually transmitted infection

People who have experienced ACEs are also more likely to have children who experience ACEs.

In populations considered vulnerable, these statistics tend to be higher due to higher rates of trauma and adverse childhood experiences.

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, who experience layered trauma of colonialisation, racism and intergenerational trauma, signs of trauma are visible in suicide and self-harm rates, alcohol and drug use and more.

Changing these behaviours is possible, but it is difficult to do alone. Our brains and bodies have to trust that we are in a safe environment. One safe experience, one raindrop, is not enough to build this belief. We need repeated experiences of safety, of met needs, and of kindness.

This is why we are asking our community to become trauma-aware. The more people involved in helping all our community feel safe the quicker our community can heal.

Resilience

Resilience is our ability to come back to ourselves after an adverse, stressful, or traumatic experience.

Some liken resilience to a tree. Trees need to bend in the wind, so they don’t break. But when the wind stops, the tree is straight again.

Being resilient doesn’t mean we don’t react to adversity, stress or trauma. It means that we can come back to ourselves afterward.

Resilience is built on our environment and relationships. If our experiences have shown us that we live in a safe, supportive environment, recovery from a stress response feels safe and can be quick. These experiences include support from family, friends, school, and needs being met.

They can also include feeling connected to one’s culture and language, and, for First Peoples, connection to Country.

On a physical level, resilience is our body's ability to return to a state of calm. This means a steady heartrate and breath and a functioning digestive system. Our body recovering from stress takes flexibility which takes practice. This means that small doses of stress that our bodies recover from increases our ability to recover from bigger stressors, which builds resilience.

If our stress response is overactive from a young age, flexibility, or resilience, can be harder to develop.

Post-traumatic growth

Post-traumatic growth is when healing from a potentially traumatic event leads to a more enriching life. This is like Kintsugi, the Japanese art of mending pottery with golden lacquer. When we put the pieces back together, the cracks do not go away. Instead, they are turned into something meaningful, beautiful even.

Five areas of post-traumatic growth:

- Improved relationships

- Increased personal strength

- Recognition of new life possibilities

- Enhanced appreciation for life

- Spiritual development.